Planetary Boundaries and the Cultural Mandate of Genesis 1:28

And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

— Genesis 1:28

When practising exegesis, it is important to consider nuances and avoid myopic interpretations of the Word. Accordingly, Genesis 1:28 deserves significant debate within the contexts of both the individual verse and overall biblical narrative. What should subduing the Earth and having dominion over all living things actually look like? As several passages of scripture encourage peace and generosity, it would be irresponsible to construe the cultural mandate as purely supportive of planetary exploitation. Colossians 1:16, for instance, emphasises the sovereignty of God, asserting that “all things were created by him, and for him” (King James Version, 2014). Comparatively, Ezekiel 34:2–4 condemns selfish behaviour, admonishing shepherds for feeding themselves while failing to heal the sick and mend “that which was broken” (King James Version, 2014). Such excerpts suggest that Genesis 1:28 does not strictly imply a call for men and women to dominate creation: the Bible’s teachings of love and redemption ultimately complement the cultural mandate, affirming the sanctity of life while fostering harmony between nature and humanity.

At the beginning of this semester, I began reassessing the Bible. I’ve never read the book in its entirety; however, now as a thirty-five-year-old man, it’s likely a good idea to properly explore my spirituality. Dissecting Genesis from a more mature perspective has been especially meaningful: as a biology student, I can apply a better appreciation of science to the story. For instance, not terribly long ago, I imagined that Genesis 2:7 involved a pillar of dust rising from the earth and taking the shape of Adam. With respect to the endosymbiotic theory (Wallin, 1923), I now believe that dust could refer to microorganisms. The idea of such an inadequate origin may seem a bit unsettling, but science has shown that trillions of microbes, such as those of the gut microbiota, are essential to human metabolism and neurological development (Goyal et al., 2015). Accordingly, there is nothing subhuman or sacrilegious about the concept of a unicellular eukaryote engulfing a mitochondrion and evolving over millions of years to become the first man.

The notion of dust as metaphor provokes further implications. In Genesis 3:14, God curses the serpent, declaring, “Upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life” (King James Version, 2014). If the dust of Adam’s unrealised flesh can allude to formlessness and disorder, then God’s polemic against the serpent indicates that Satan was sentenced to thrive perpetually on chaos. As a follower of Christ, preventing turmoil and promoting salvation should be primary pursuits. Admittedly, I feel like a bit of a religious nomad, but I do have faith in Jesus, and I definitely recognise the miraculous beauty of God’s work. Although death and decay are inevitable in this fallen world, we should circumvent unnecessary suffering as much as possible. Without Christ’s return, paradise is unachievable, but we should at least bloody strive for it.

So, when I scrutinise Genesis 1:29–30, which immediately follows the cultural mandate and describes a diet of plants for both humans and animals, I observe the proclamation literally. Although I concede that hunting remains culturally significant and crucial to survival in some situations, I am nearly convinced that blood, bone, and sinew did not become food until after Adam’s downfall. Much of the world could abolish meat and obtain sufficient nutrition through vegetables, legumes, and supplements (Mann, 2009). Again, reviving Eden is impossible, but we can try to replicate perfection and respect the garden’s memory. For me, that process demands an end to animal cruelty and needless slaughter. It’s difficult to express that sentiment without sounding judgmental or condescending; however, I mean it from a place of empathy. As Susanna Wesley said, “Whatever weakens your reason, impairs the tenderness of your conscience, obscures your sense of God, or takes off the relish of spiritual things—in short, whatever measures the strength of your body over your mind, that thing is sin to you” (Kirton, 1884, p. 27). Essentially, I acknowledge that my sins may be different from those of other sinners. Unless your gut is telling you that eating meat is immoral, perhaps a diet of flesh is completely appropriate.

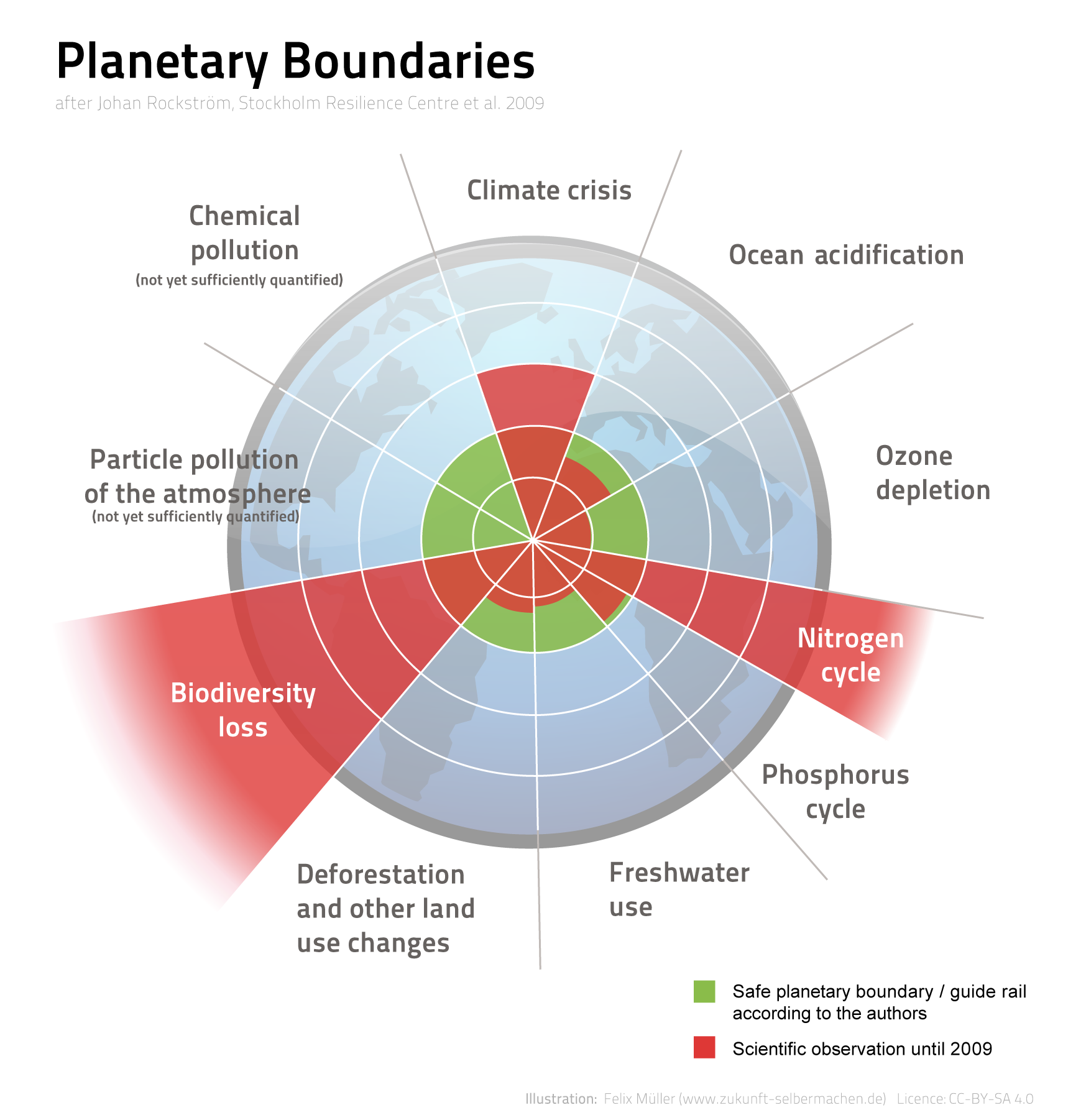

Nevertheless, the planetary boundaries make it glaringly obvious that the world needs considerable help. Awareness engenders obligation, and because we know of ocean acidification and biodiversity loss, we must embody the cultural mandate and participate more rigorously in delaying the Earth’s destruction. I can certainly do more to reduce my ecological footprint: the university’s a twenty-minute jog from my home, but I still take the car to school. Regardless, actions such as minimising fuel consumption are not good enough. The planet requires more effort, and passivity will make us exceptionally complicit in premature disaster. When it comes to the world’s protection, negligence and indifference are as reckless as sins of omission. With so much to do, wasting time is thoroughly wrong. Through nature, fitness, knowledge, and love, we need to become formidable and contribute to this planet as effectively as possible.

References

Goyal, M. S., Venkatesh, S., Milbrandt, J., Gordon, J. I., & Raichle, M. E. (2015). Feeding the brain and nurturing the mind: Linking nutrition and the gut microbiota to brain development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(46), 14105–14112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26466405

King James Bible. (2014). Hendrickson Publishers Marketing.

Kirton, J. W. (1884). John Wesley: His life and times. Morgan & Scott. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/60214501

Mann, J. (2009). Vegetarian diets. British Medical Journal, 339(7720), 525–526. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25672532

Müller, F. (2014). Planetary Boundaries [Illustration]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Planetary_Boundaries.png

The image is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Wallin, I. E. (1923). The mitochondria problem. The American Naturalist, 57(650), 255–261. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2456429